Here I am, away from home, a relative rarity. This is likely the last summer that we will have both kids living with us (I hope I’m wrong, but I’m trying to prepare myself for an eventuality) and to make the most of it, we planned a real Family Vacation. It’s just the four of us staying in a little house tucked into the shoreline of Maine for four days—taking short hikes, cooking meals together, listening to terrible music as we explore nearby towns. We’ve had a real “get away from things” intention, which means we’ve focused on birdsong instead of Twitter, and napping instead of news. At home we have each been experiencing life as deadline after deadline: college applications, book proposals, healthcare forms, strategic plans. In Maine, we’ve accepted our slowed-down time together with a willing suspension of disbelief.

The shooting at the Trump rally broke through our bubble, a reminder that the world still turns whether or not we are willing to acknowledge it. The shooting and Trump’s announcement of J.D. Vance as his running mate have brought my sense of underlying dread right back to the forefront, unwelcome but impossible to ignore. The Democratic leadership seems unable to land on a unifying message, even as we voters seem crystal clear on the job at hand. The political state of our country is fractured and devolving, and it feels as though it’s by design: things are beginning to spin (or to be spun) out of the control of the masses.

I’ve been reading a lot lately about the 1920s and 1930s, trying to get some context for letters and short stories written by my grandfather. I gravitate to readings that paint a picture of the popular culture, and try to avoid pieces that focus on the roots of World War II. I learned plenty about the war as a kid, both formally and through osmosis; references were everywhere and defined each generation (pre-war, Greatest Generation, post-war). When trying to reconstruct my grandfather’s early life, WWII feels like the elephant in the room that obscures my view of everything else. I’ve been looking around it and under it and behind it in order to understand his other cultural references, which feel lost to or subsumed by post-WWII perspectives. I’ve been trying, I suppose, to bring a more innocent time back into focus.

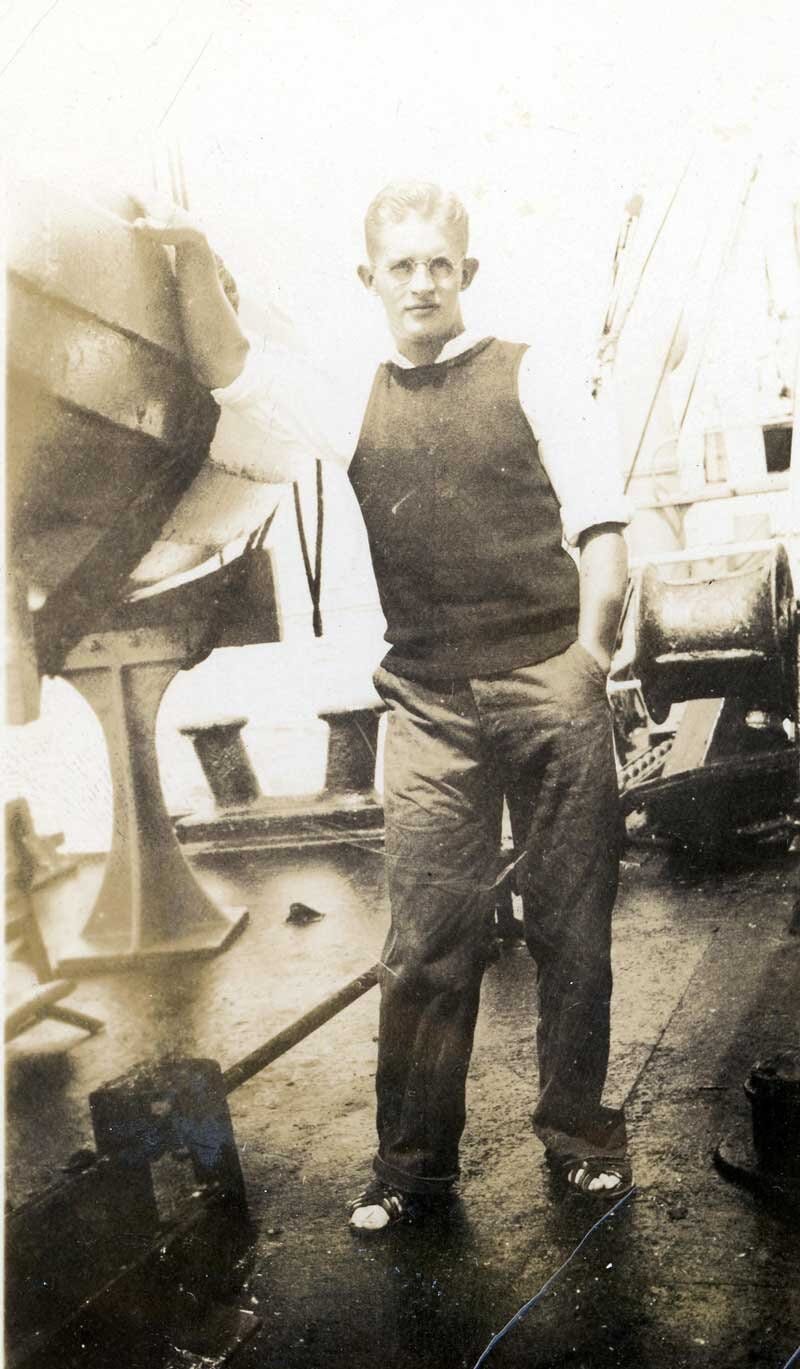

Honestly, hunting down the pop culture of 1935-1936 Paris has been fun. As a young journalist there, my grandfather was often assigned to report on visiting sports celebrities and movie stars. He chased boat trains for stories and profiled literary greats. According to him, Douglas Fairbanks “sounded like an illiterate 33rd street tough;” Marian Anderson “was the pleasantest interview I think I have ever had, and one of the nicer persons I have met;” Marlene Dietrich was “so busy being aloof that she forgot to act human and say hello.” Meeting Alice B. Toklas (“her appearance and voice all seemed to carry vague echoes of a New England spinster”) and Gertrude Stein (“I should like to go back again and talk with her, if I were presumptuous enough”) changed my grandfather forever—he still spoke of it decades later.

If you track down all the names my grandfather drops in his letters home, you can piece together a thrilling mosaic of the pre-War Paris high life. At the same time, it’s an impossible job to separate those amusing stories from the rumblings of chaos and discontent that were growing all around him, both in Paris and beyond. That chaos is just as intrinsic to my grandfather’s letters, because both visions of Paris were true.

Still, for many the two Parises only existed in parallel. As my grandfather wrote in June of that year:

We continue to have, as you saw in the newsreels, policemen chasing rioters all over the streets. It’s surprising, however, how much can be going on around you and you never know it. […] It’s as though you were at work in Wall Street in New York while bloody riots were going on in Harlem. The only way you’d know would be through the newspapers. I’ve only seen a couple of minor riots since I’ve been in Paris, and there have certainly been enough of them. During the terrific riots they had here in February 1934, in which streets were barricaded and thirty or forty persons killed, people were sitting on café terraces up in Montparnasse looking at the sky, all red with the reflections of bonfires all over the city, and sipping their coffee in quiet and reading the papers about what was happening.

It’s all too easy to compartmentalize and reassure ourselves that things are normal—even that things are good. I am sitting on a wooden deck overlooking a sleepy cove in Maine, drinking an ice-cold seltzer. The sun is on my back, and I’m listening to a mockingbird show off. But right now, with news of Trump impossible to keep at bay (still? again??), I can’t shake the memory of a passage in a letter my grandfather wrote to his parents after reading Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 work It Can’t Happen Here:

The picture he draws of an unscrupulous demagogue of a politician riding to the White House on a flood of impossible promises is too true to have the slightest element of humor. The book isn’t meant to be funny, but I don’t imagine even Lewis knew what a shocker he finally turned out. When you see a picture of the United States in the hands of a crew of plug-uglies, with concentration camps, suppression of all personal liberties, frantic screamings about ‘New culture’ and all the personal trademarks that denote Italy and Germany in the public mind, it makes your sleep restless. It did mine.

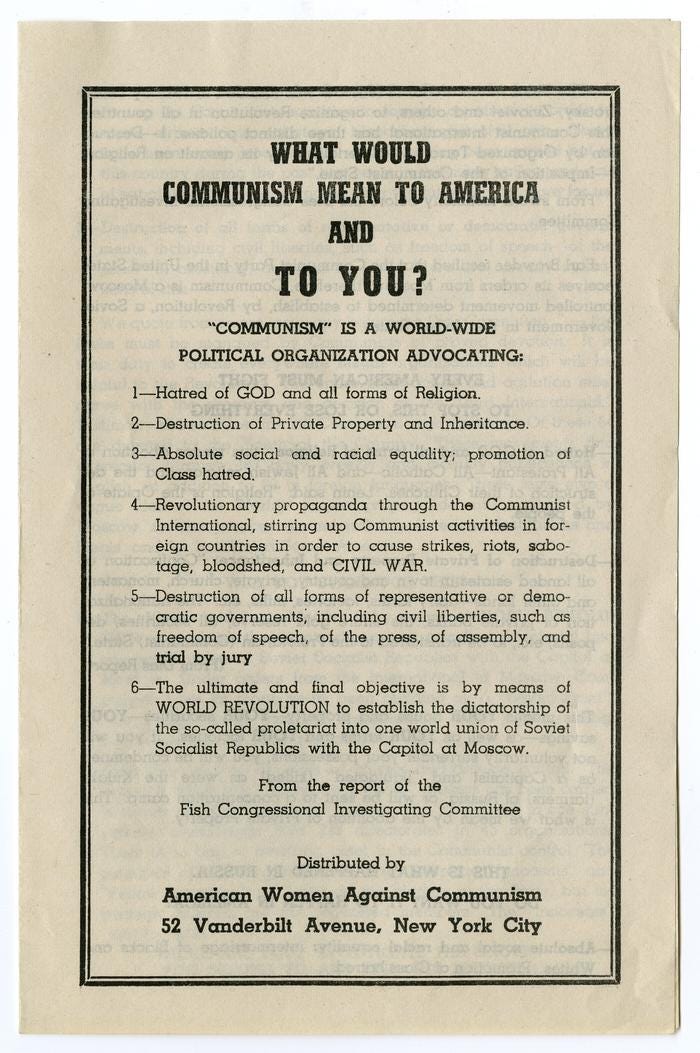

A few months after he wrote this letter, my great-grandmother forwarded my grandfather a pamphlet entitled “American Women Against Communism.” It was one of a series that were being distributed as soft propaganda by fascist sympathizers in the United States. From his viewpoint in Europe, my grandfather recognized imminent danger.

Only 22 years old, he responded to his parents with an urgent plea for them to reject the soft-sell of hateful rhetoric:

When I get a letter from my family that reveals a high degree of political passion coupled with a growing intolerance, I not only am tremendously disturbed and upset but actually alarmed, because I know it’s not centered in my family alone, but is indicative of the way hundreds and thousands of persons are thinking and feeling. […] Magnify that little brochure a dozen times or so and what you get is the Black Legion creed or something akin to it; against communists, against Jews, against Catholics; against aliens, and strongly in favor of that vague thing called Patriotic Americanism, which means you have God-given right to stamp out anybody and anything that doesn’t conform to your principles, even if you yourself may be an intolerant megalomaniac.

History repeats. As surely as democracy in Europe was threatened in 1936, we now face a terrible crisis here in the United States. I know that we are more distractible than ever—Kardashians attending billionaire weddings, Katy Perry’s terrible feminist (?!) video, our summer vacations—but that elephant isn’t going anywhere. It has always been in the room, and it’s still standing right there in front of all of us. Until we look straight at it, until we decide how to handle it, things aren’t going to be okay.

The "What Communist Would Mean To You" sounds eerily familiar to the current Biden administration

where God and religion are often considered "radical," the promotion of absolute racial and class equality (DEI) are policy, and class hatred and the curtailment of civil liberties foundational to our democracy are everyday ocurrences, Equal justice is not guaranteed for all and citizens are fearful to express their opinions.