When my grandfather was 22 and fresh out of college, it was 1935. The world had “recovered” enough from one Great War to be teetering on the brink of the next; the United States had scraped through the financial crash of 1928, yet was poised to sink into the Depression. Fear of communism meant that many Americans were prepared to cast a tolerant eye on fascism, even as Hitler prepared to invade the Rhineland. Amid all this, Laddie was a young man of privilege who wanted to see more of the world.

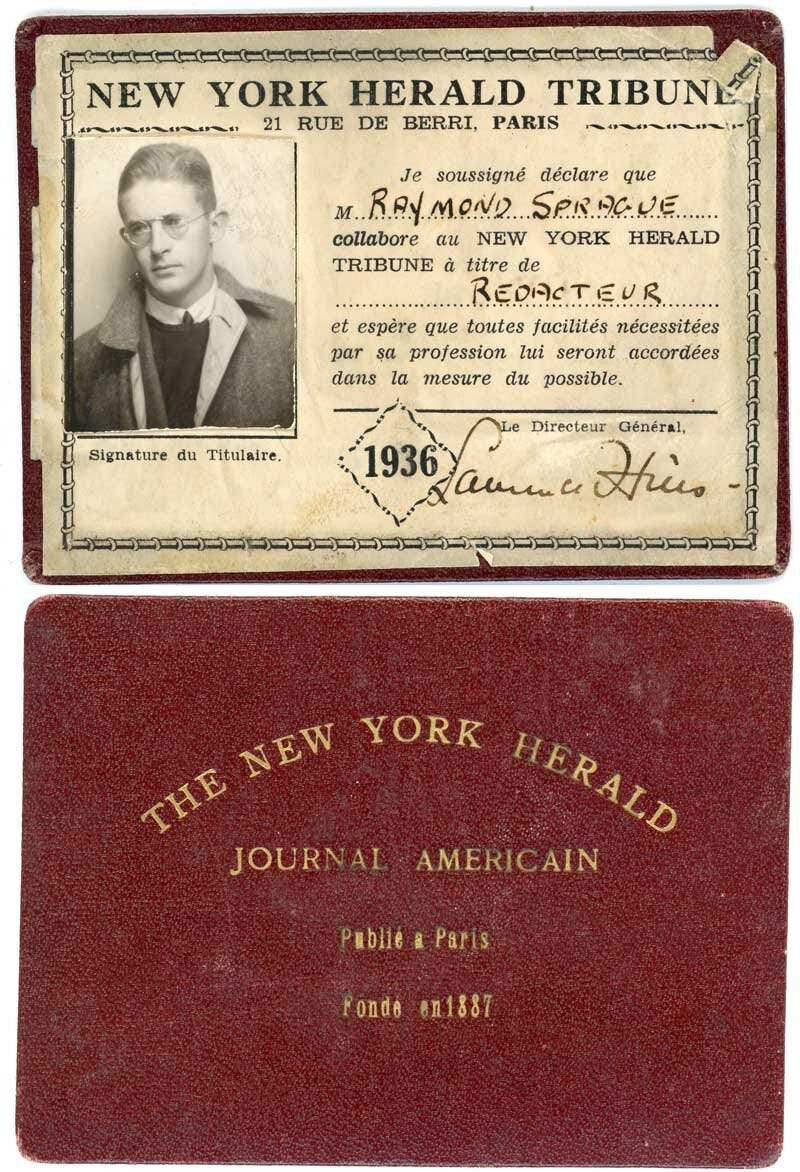

For roughly a year following his graduation from Williams College, my grandfather would work as a young stringer for the Paris Edition of the New York Herald Tribune. From August 1935 to September 1936, Laddie sent (mostly) typewritten accounts from Paris to his parents in Greenwich, Connecticut. Although he typed a few letters from the Herald’s offices at 21 Rue de Berri, only a few minutes’ walk from the Champs-Élysées, he usually composed them at his boarding house nearby. Sitting in his gaudily decorated room (“this chamber of pink horrors”), he would describe colleagues at the iconic paper, the social unrest rocking Paris and Europe, chasing interviews with celebrities of the day, and his struggles to become a Great Writer.

Fifty years after writing the Paris letters (they were then tucked away at the bottom of a trunk), my grandfather joined my mother and me for lunch at a small restaurant near Hillsboro, New Hampshire. I had just completed an academic summer program and was entering my senior year of high school. The three of us talked of college essays, summer and family, favorite memories. My mother made a casual remark about Grandsir’s feelings on a topic I can no longer recall, but I remember clearly how he answered her with uncharacteristic sharpness.

“You don’t know me at all,” he said tersely. “You only know what I’ve told you.”

We were both taken aback. Grandsir tended more to humor than reprimand, and there was no lightness of tone here. My mother cautiously acknowledged his comment, and we carried on the lunch with just the briefest of hesitations. Driving home later, my mother and I wondered whether his rebuke had been rooted in loneliness (my grandmother had died two years earlier). Yet there was more to it for me, and I would carry the moment with me for the rest of my life. It felt like a reminder that isolation constantly threatens; it fueled an urgency to find connections.

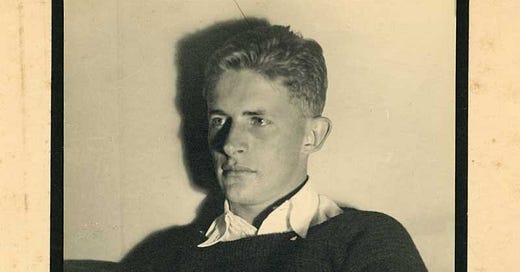

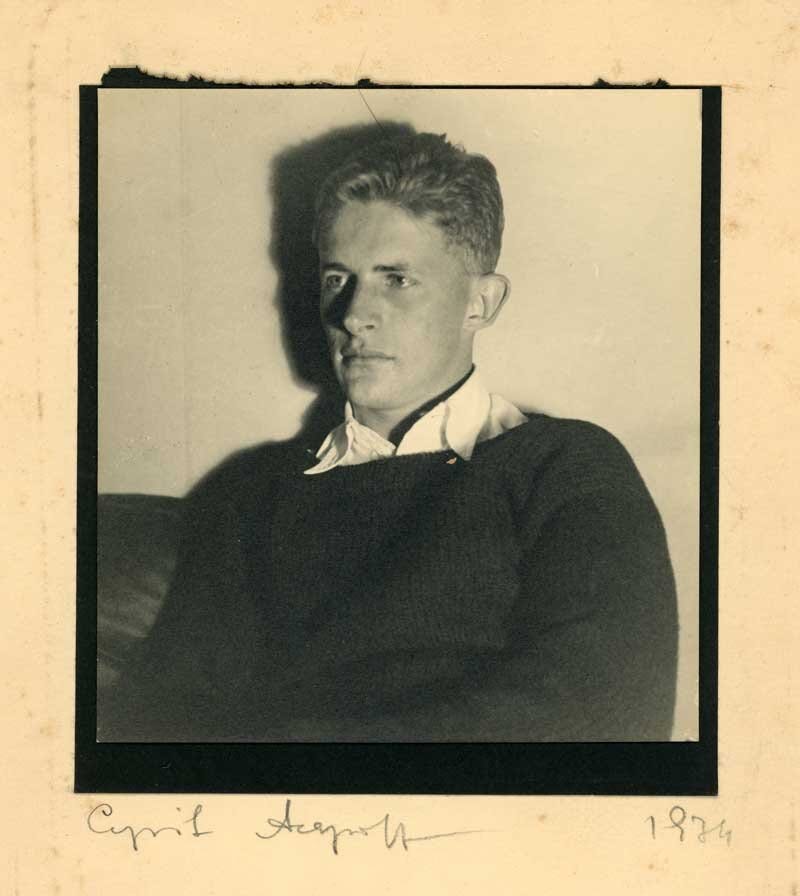

That is why, when I came across Grandsir’s letters from Paris after another 30 years had passed, the sense of direct connection was almost breathtaking. Grandsir as a young man, Grandsir writing to his parents, Grandsir as Laddie, seemed to offer the possibility of insights that I had thought impossible. The letters provide just a snapshot from a particular point in time, but—although he would be changed by later life—Laddie was still a part of Grandsir.

Recovering the Paris letters has felt almost impossibly timely. Much of what what my grandfather observed there nearly a century ago seems to resonate with our current chaos. I’ll be sharing excerpts here, as they feel particularly on point. Perhaps they can teach us something, or at least underscore the parallels.

Apart from any historic significance, it’s been a gift to meet my grandfather as Laddie, just as my own sons approach the same age. During such a turbulent era, my grandfather must have felt uncertainty about the future, and a certain cynicism about human nature. My boys share those feelings, as surely as they share his energy and his humor. Reading the letters, I feel struck over and over again by my grandfather’s struggle to find purpose; by his transition from a teenager’s self-involvement to a young man’s sense of duty. My heart hurts for the war that lay ahead of him, but the letters show me that Laddie already had strengths to draw upon. He makes me laugh; he makes me proud. And—for my own boys—he gives me hope.